The writers of Matt Cardle’s hit, “Amazing,” are suing Ed Sheeran for copyright infringement because his much bigger hit, “Photograph,” sounds too much like their song.

Here’s a mashup that proves not a whole lot, but you’ll get the idea.

I’m also not automatically impressed by claims about how many notes two songs have in common or the well-worn, “gazillion to one!” probability calculations that get offered, et cetera.

But honestly, 39 is a lot, if it’s true.

And before we get into the musicology, in case you’d care to skip it, I’ll tell you how this ends: I would strongly recommend to Ed Sheeran that he cut a deal.

UPDATE: 4/10/17 It looks like he did.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/ed-sheeran-settles-copyright-lawsuit-photograph-992354

We are going to take the complaint, line by line pretty much, and evaluate the claims, right after I make a bunch of soapbox general arguments.

Ed Sheeran, in case you’ve been in a cave for a while, is a superstar singer who writes pleasant pop songs. Excellent ones — thoughtful, cute, and well-crafted. His “Photograph,” is thoughtful, cute and well-crafted. And indeed, it sounds a lot like “X Factor” winner Matt Cardle’s “Amazing” — more than “similar to the ordinary observer.”

But while any ordinary observer can certainly say for herself if she thinks two songs sound similar, not all similarity is significant. Insignificant similarities would include compositional banalities that are public domain or otherwise not protected by copyright. Also, they would include musically ambiguous devices, like “vibe,” and recording, production and instrumentation techniques — these largely do not support a case for copyright infringement. They do however sound awfully fishy to the ordinary observer.

Led Zeppelin, for example, recently won its copyright lawsuit. That jury decided that “Stairway To Heaven” did not infringe upon Spirit’s “Taurus.” Those two songs sounded a lot alike too. Musicological analysis by Musicologize determined that the jury’s decision was correct. We can try to predict how this one will go. Let’s look at the plaintiffs’ argument, apply some musicology, and get to the truth.

First, I don’t watch X-Factor and I’d never heard the Matt Cardle track before this plagiarism suit arose. The allegedly infringed upon work, “Amazing,” is a well-crafted song and its songwriter plaintiffs Martin Harrington and Thomas Leonard are pros with a notable track record.

Their complaint is right here, so let’s assess it. The plaintiff’s claims are shown below sometimes as paraphrased/interpreted by me to cut through some legalese and other times they’re presented verbatim. They’re in bold, and my opinions follow in italics. Sorta like a question and answer format.

Here we go…

Plaintiffs: The chorus is very important to the song.

Talk about “laying the groundwork.” You wouldn’t even think it needs to be said. Yup. Important. Sure is, especially to “Photograph,” I might add. And this matters, because it factors into the damages calculations.

The defendants intentionally and unlawfully copied the unique and original chorus from “Amazing.”

Maybe! The originality and uniqueness of “Amazing” is arguable. And intent to plagiarize is a big leap. But despite this being a “maybe,” as I’ll explain later, this leap is an appropriate tactic. When you bring a copyright lawsuit there’s a bunch of stuff you do just because it’s what you do.

The choruses share 39 identical notes plus 4 other pretty darn close ones out of 64 total notes (70%).

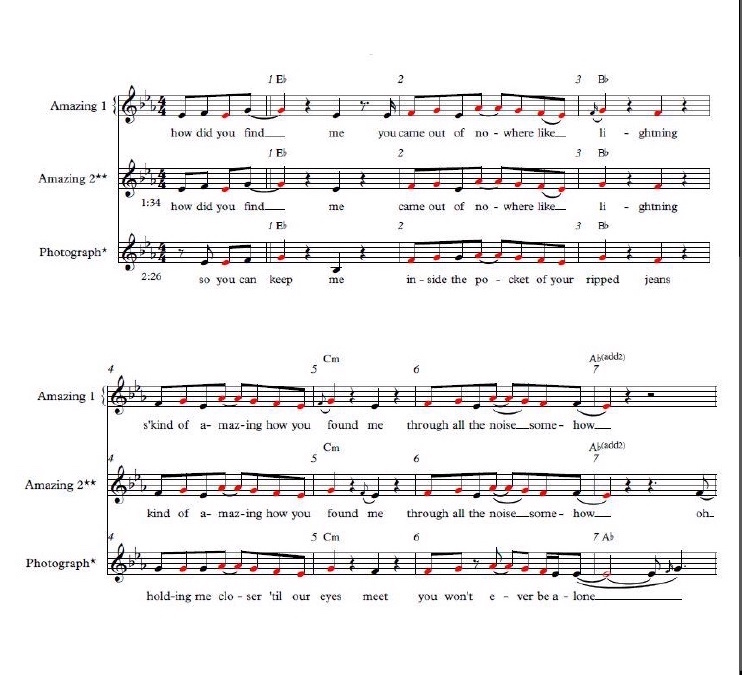

This is the crux of the “on paper” argument. This sort of headline number is overemphasized too often when we look at copyright lawsuits. Yes, there are lots of identical notes as the notation they provided (below) shows very clearly. As often as not however the raw numbers mislead and this is an area where a musicologist can illuminate things in service of either side’s argument.

For example, see those first few notes, not in red? Collectively these are just a “pickup” — notes whose specifics are relatively less important that introduce and lead up to a much more meaningful note — the fourth one in this case. Importantly, these and nearly every other still black note on the page are what I refer to as “low-value notes.” They matter very little to the “MEANING” of the musical phrase. They may or may not be identical pitches on identical beats. They don’t make much difference. These are inconsequential note choices often as in this case chosen to support the peculiarities of the respective lyrics. These notes could be altered, embellished, or omitted and it would make very little difference to the song. And they make little difference to the songs’ similarity. Most of these low-value notes could even be exchanged or traded between the two respective choruses, and the choruses’ respective recognizability would be almost completely unaffected.

That sounds important.

How is that possible? It’s possible because of the very high value of other notes. High-value notes are often the essence of the infringement.

In fact I think the plaintiff’s claim that the two songs are 70% identical is actually understating how alike these two tracks are.

They include this sheet music in the complaint and they’re absolutely correct that all the red notes are shared by both songs, and black notes not precisely shared.

I would argue that there is only ONE high-value note that’s different in the two choruses and it’s not terribly different. Which is it? Can you guess?

It’s that quarter note on the third beat of the chorus’s first measure (not the pickup measure, the next one, labeled “5.”) The lyric is “me.” There’s almost no refuge for the defense in this critical note being a different pitch. Harmonically and melodically “Photograph’s” fifth scale degree here is THE MOST CLOSELY RELATED DIFFERENT PITCH AVAILABLE compared to “Amazing’s” third scale degree. Musical notes are not simply “alike” or “not alike.” Notes are like colors. They can be complementary or analogous. Like language, notes can be synonymous or antonymous. There are only 12 notes and here, of the eleven other choices, Sheehan’s note is the least different.

But the way, this note is a high-value note because of its location in the chorus and because of its lyrical, rhythmic and cadential treatment. It’s emphasized in every musical way. It’s actually one of the two highest-value notes in the whole track – not identical, but as close as it gets.

This next one is almost humorous. Perhaps it’s in the boilerplate.

Both the “Amazing” chorus, and the infringing “Photograph” chorus, utilize similar structures (both have verses followed by bridge and chorus sections), and the first chorus of each song is half as long as the chorus sections that follow.

That’s true of nearly every pop tune, people.

The chorus of “Photograph” is 41% of Photograph.

This is similar to their “the chorus is important” point. But it’s interesting because this isn’t really a part of the “they stole our song” argument. It’s really setting up the damages calculation. They’re will argue that they’re entitled to up to 41% ownership of Sheeran’s track. They’ll further argue that it actually should have a multiplier applied because it’s the hook. “The chorus is important,” they said. But for now, they’re getting it out there that it’s at least 41% of the notes on paper.

The chord progressions are essentially the same. There’s one chord that’s different, and it’s not very different.

True, they’re the same as one another. They’re also the same as a great many other famous pop songs. In fact, it might the most common progression in modern popular music. And as it was with the red and black notes of the melody, the one not-quite-red chord in the progression (imagine pink in your head, because we don’t have a graphic) is not very different at all.

Quick bit of theory. Chords, like notes, can be analogous. In the one spot where the chords are different, the chord in “Photograph” is what we call a “V” (five) chord. “Amazing’s” is a “iii” (three) chord. (Upper case roman numeral denotes “major” chords, and the lower case denotes “minor” chords.) These two chords just happen to have more common pitches than distinct ones and function similarly in the progression. So they’re very analogous as the complaint points out.

We often hear it said during these copyright lawsuits, “You can’t copyright a chord progression!” and no, indeed you can’t. But chord progressions are harmony in motion, and combinations of melody and harmony are expression. And expression has intent and meaning just as words taken in context are more often what you “meant” and not merely what you “said.” That expression, intent, and meaning is specific, definable, and copyrightable. So while the chord progression is not unique, and chord progressions in a vacuum are not protectable, they’re still part of a relevant argument for the plaintiff.

The chorus section of “Photograph” uses the same rhyming structure as the chorus section of “Amazing.” The measures 1, 5, 9, 11, and 13 all end in a similar “ee” sound. Measures 1, 9, and 13 actually end in the same word (“me”).

They’ve moved over to talking about the lyric now and their claim is obviously true. It’s the simplest argument again, just the sheer number of alike occurrences. Here again, there are higher value moments and lesser value moments. They should stress the “me’s” that occur in measure 1 and measure 9 which predict or even dictate the “ee” sounds and “me’s” to follow. The two largely identical choruses are built from the same basic very similar building block. “See me,” and “Keep me,” respectively, sung in descending pitches on beats one and three — alike signature moments in both songs and the essence of the work!

Hey look, they’re about to say just that.

“The songs’ similarities reach the very essence of the work. The similarities go beyond substantial, which is itself sufficient to establish copyright infringement, and are in fact striking. The similarity of words, vocal style, vocal melody, melody, and rhythm are clear indicators, among other things, that “Photograph” copies “Amazing.””

Good for them. They sum it up quite well here. This is the strongest position — that the essence of the songs are identical. The high value notes are identical and so the “intent and meaning,” as I like to say, is musically identical. And so it’s infringement! The works are indeed substantially and essentially alike not just to an ordinary observer, but to an expert. That should be more than enough.

But “enough,” can vary from case to case. In copyright lawsuits, “enough” is somewhat a function of the defendants having had access to the song they duplicated, and whether they intentionally infringed. In other words, if Sheeran never heard “Amazing,” then the threshold for infringement moves a ton. And so you get arguments like the following…

(Defendants)… had access to the “Amazing” musical composition through (radio, youtube, etc). In addition, as discussed below, the sheer magnitude, and verbatim copying of “Amazing” by Defendants, is so blatant in both scale and degree, that it raises this matter to an unusual level of striking similarity where access is presumed.

Yes, “Amazing” cracked the Top 100 in the U.K. and had a million views on YouTube as of June 2016. But I’d never heard it. And I’ve got more free time than Sheeran.

They go on to say that it’s assumed Sheeran had heard “Amazing,” because otherwise how could such a blatant ripoff have occurred?

No. And they should have to give back one of the millions they’re going to get for being so circular.

That’s right, they’re going to get a lot.

All in all, the plaintiffs are quite right about everything.

Back of the napkin, I would make the argument that “Photograph’s” chorus comprises as much as 70% of the song’s total value, much more than the 41% implied by one of the plaintiff’s complaints; “Photograph’s” lyric though is particularly key to its chorus and therefore the song’s total value. Those lyrics are at most inspired by “Amazing.” I would calculate the infringement — the notes, chords, rhythmic treatments, etc. — to be no less than 50% of the chorus’s value. Therefore “Amazing’s” owners are entitled to 35% (half of 70%) of the profits from “Photograph.”

Calculating those profits is near as fun as dissecting the track itself. No, actually it’s not fun at all, but if you’re going to argue infringement that’s where these copyright lawsuits eventually have to go. Forensic accountants gotta eat.

The actual complaint is on Scribd, and it describes all the places the plaintiffs threaten to send their forensic accountants to find “Photograph’s” profits. The value of music has many more tentacles than most realize. Check it out at https://www.scribd.com/document/315183509/HaloSongs-Inc-v-Sheeran

1 Comment